If you do not live in a temperate, coastal location with high rainfall, you may not know about the midge. You see, the midge is a wee blood-thirsty beastie which rises in late May and spends the next three to four months feeding on any piece of exposed flesh available to it.*

*Please note: Midges occasionally drive their victims to using bad language, and this post is no exception.

The midge bite is small but persistent, itching out of all proportion to the size of the mandibles which cause it. Or at least this is the case for the first three years of exposure – which is no use to visitors of course, but explains why West Coasters born-and-bred barely bat an eyelid under the onslaught of these multitudinous airborne pests. Because, while the bites are an incessant irritant after the fact, the initial onslaught can be truly excruciating.

Imagine an early summer evening, when the light is limpid and louche, falling toward a gentle, welcoming darkness – soft in the virtually tactile way that only the ocean ward coast of Scotland can produce.

Imagine that you are coming home to your newly finished, glorified garden shed after a weekend away with friends. It’s just the two of you, content to come home after a long journey full of conversation, insight and laughter.

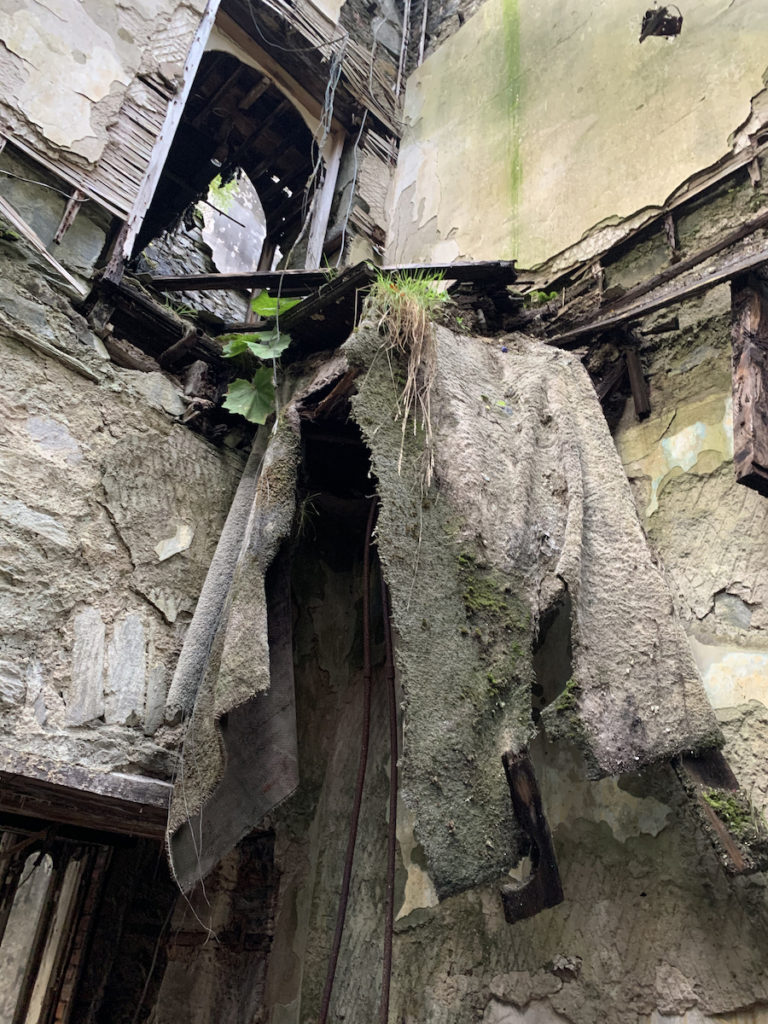

You turn your battered soft top Vitara into the drive and allow gravity to take you down to the bridge. You want to keep the car’s progress slow because the unfinished drive rocks the short-wheelbase of the four-by-four such that your already sore backs will be further jarred (the Vitara was never a comfortable ride), and you note as you cross the bridge that the castle is looking particularly pretty, the tops of the chimneys are caught in the last light of the setting sun, and the foot of the ruin seems to accentuate this by being sunk in a deeper, darker shadow than you’d expect. Both of you glance at the stand of tall trees across the ravine from the castle to see if they account for the visual contrast, but nothing unusual strikes you.

The slight rise to the last corner wakes the bassets who immediately become animated with home fever. You glance at one another and smile, anticipating much low-slung and hilarious scooting around by the doe-eyed duo as they reacquaint their patch with them. The drive levels out, and you slip quietly down the avenue of, on one side, overgrown Leylandii and on the other five gargantuan exotics – led by what has come to be known as the ‘Harry Potter’ tree – although I am sure it looks nothing like the Whomping Willow. It’s nearly fully dark under the trees and you put on the headlights. They meet a thick veil of insects which move in mildly hypnotic wave delineating the full beam of the lights to their utmost extent 200 yards away to the foot of the castle. You glance at one another not quite understanding (a) how such insect-life could have arisen in the 72 hours you have been away and (b) amazement at the fecundity of nature even in these hills where the ground is notoriously poor, water-logged and inimical to anything other than pine, rhododendron and rashes.

Imagine that despite your wonder at this sudden irruption of natural phenomena into your life at Dunans, you allow your car to coast at approximately 2 metres per second down the drive and into the gravelled embrasure on which the red shed stands. The quality of the light improves and you see that the entire foliage delimited quadrangle is thick with a floating mass of insect-life fluctuating to an altitude of about 8 feet. It is at this stage, when you slow the car to the point that it will roll at, maybe, half-a-metre a second to its place before the shed, that two things become apparent. First, the canopy of the soft-topped car, which covers boot, rear seat and ceiling above really isn’t airtight, and second that driving so slowly means that this wondrous, slowly and softly dynamic layer of insect-life is in fact able to find admission into our coolly comfortable capsule of car air.

The time between the slowing and the screaming was perhaps all of 5 seconds.

When the red mist of midge rage descends rational thought becomes absolutely impossible.

The bastards bite.

The bastards get into your ears.

Into your nose.

Up your nose.

Into your eyes.

The creases at the corners of your eyes.

You scream. You run. You swear. You slam doors.

You open doors to let the dogs in.

You remember your baggage. You remember the shopping. The milk which needs the fridge.

You swear. Find a balaclava. Run out to the car. Get the shopping bags.

The milk bag splits. The cartons spill over the drive.

You swear. You cry.

You pray to God that the Balaclava is working. It isn’t. You throw it off.

You scrabble for the milk.

You weep.

You run in.

Throw milk at your wife.

Return outside for the bags.

You are hollering like Rambo. And choking on midges.

And still running.

Doors slam more.

There’s the tinkling of glass.

You run in. Slam the door.

Drop the bags.

Look at your wife who is scrabbling at one of the windows.

The windows.

They are covered in midges.

Billions of them.

We can’t see out.

And some of them, some of these bastards are on the bastarding inside.

An hour later we find ourselves sitting in the dark, in close proximity to two floor standing fans and one desktop fan in the centre of the red shed. We are trying really, really hard not to scratch ourselves. I am trying not to weep. My lovely wife is holding her head her hands, her jaw set. I can see she is calculating our next move. I cannot hold my head because my hands are covered in a mixture of silicone sealant and midges. I have a cut across one of my hands where the scissors slipped as I cut organza fabric, and at my feet are several thousand unused staples, an industrial staple gun and all the plasters we own. We know we have to venture into the bedroom to fight the midge invasion, and we also know that because of the variable level of the foundations, there is a big (bastarding) gap between wall and window bottom in that room. We look at one another and ask simultaneously, “What the hell have we done?”

That first year, in the hut with single-glazed windows of approximate fit, without airlock (AKA porch) for the shaking out of insect-life from hair, clothes and dog, without any through-breeze onsite of any kind, the midges were sanity-threatening awful. If I have subsequently called the castle a glorified mouse-breeding box, then the rash-filled paddock next to the red shed, with its sundry hollows, its deeply scored quad bike tracks, the miscellaneous divots and other depressions, all causing the retention of water to the point walking in it required waders, was similarly termed the midge-breeding box. We identified this area as the main problem and that was where we focussed our attention, to begin with.

To wage a successful war against the midge one needs to remember two things: first, this is a long-term campaign and second, there are no short-term solutions. You’ll also need to remember two further things: first, as alluded to in our very first swarming encounter, midges cannot withstanding a breeze of more than one point five metres per second, they are literally blown away, and second, they are crepuscular.

You can walk a swarm off – they literally cannot keep up. If you spot several Scots in a field having an agricultural chat, they’ll not be leaning on a five-bar gate (mostly because three of the five are rotten and the top is so patched with scraps of kindling that its actually quite uncomfortable to lean against) they’ll be walking in an ever-increasing spiral. Obviously, you’ll not want a decreasing spiral because the Pygmy flies will then end of concentrating in the correct space. Also, these voluble West Coast farmers, because, believe me, they can be very voluble, will avoid their livestock. Livestock generally have their own domestic swarm, a colony of midges, who for the summer describe a cloud or halo around their chosen beast.

Now concerning the crepuscular element of the equation (while ensuring we reference the Fire Sermon as the only reason I had any notion as to what this poly-syllabic term meant before the advent of midges into my life) the reasons midges are dusk and dawn-favouring are two-fold, first, the lack of sun. They, like moles, mice and marmots do not like direct sunlight. Well, mice might, but they prefer cover from marauding predators than full sunlit exposure. Not having researched the subject, I am not sure why midges don’t like sunlight, but (vast) experience shows this to be the case. Second, at dusk and dawn, any air movement generally falls away. There may of course be a third reason. Midges feed on blood. Any blood. They are not fussy. Human, deer, coo, sheep, dog, cat. At dawn and dusk these creatures are not wont to rush about madly, they slow, they prepare for the onset of night or begin the process of waking. The midge prey are therefore not moving at more than 1.5 metres per second, and therefore are available.

How is it you may ask that such tiny creatures can find their prey with such alacrity? Midges are attracted initially to the carbon dioxide their prey emits, then by movement, colour and odour. Finally, once a midge finds prey it emits a pheromone which attracts other midges.

It may be the pheromone which finally persuaded us that midge magnets weren’t for us. Either that, or the thought of using a can of gas every couple of months to produce a constant stream of carbon dioxide to clear a quarter acre of ground. While we awaited the effect of the changes we began soon after that tortured evening of the soul, we invested in a midge magnet. Now, quite apart from my inability to

(a) remember to check the gas canister on a regular basis

(b) empty the nets of midges as they neared full

(c ) light the magnet (once I’d managed to remember to check the canister, see that it’d been empty for some time – given the deliquescence of midges in midge-net – get to Strachur to replace the canister, order a canister because I was the only person using that particular type, forget to remember to return the following week once the gas co. had delivered said preferred type, remember a further week later to get the last canister of the preferred type given that four other households “ …. were giving these midge magnet thingies a try”).

No, midge magnets weren’t the solution, not at Dunans, not with our infestation, not with my record of replenishment and maintenance. There is a far flung corner of a shed where several hundred-pounds-worth of kit moulders paying tribute to our commitment to rid ourselves of midges and also, to our eventual success.

Note to those who visit midge-infested areas only infrequently: Do not – I repeat – do not sit around a midge magnet. It’s a magnet. Midges, seeking the carbon dioxide exhaled by animals are attracted to it – as if its a …magnet. By sitting there you’re creating a HUGE target for midges, even those outside the quarter acre of midge-free atmosphere. It’ll not be pretty. You’ll spill your beer, knock the prosecco for six, throw down your burgers in panic, trample small children – all the time swearing, “Bloody-bastarding-thing doesn’t bastarding work. You said they worked! Only reason I agreed to come here. Right, I have had enough Mildred, WE ARE LEAVING!” You will then jump into your seven year-Old Volvo and never return, even to retrieve the youngest’s purple unicorn pillow called Tilly, which a week later a family wanting respite from a midge infested patch of grounds near a castle not 20 miles away, finds in the porch, hanging rather forlornly on a coat-hook.

Over three or four years following, we reduced the incidence of midge deluges markedly, such that now, it is only of passing interest when we have a bad day. My paltry efforts, along with mighty shifts by folk like VBF, Chris, Stuart, Min and Tino, have led to policies in which it is possible to picnic, or to barbecue, in comparative comfort with only an occasional surfeit of airborne bitery. We do still dress our open windows in organza, practice a lights-out policy during late-May, June and July, as well as utilise floor and desk-mounted fans day and night.